This year I wanted to dive deeper into Ethereum’s internals; I think I got more than I bargained for. The original plan was to read the the Ethereum Book by Andreas M. Antonopoulos and Gavin Wood, then learn Yul and Huff, then re-implement OpenZeppelin libraries in Yul/Huff. And I had some interesting side-quests planned like LearnEVM , a cool written course on EVM and Charlie Harrington on Farcaster recommended w1nt3r’s EVM from Scratch course.

Well, I went the reverse order, mostly; W1nt3r’s course isn’t out yet so I started by going through the LearnEVM course. It’s in-progress and many things are missing but I understood Ethereum enough to be able to go through Yul docs. I went through Yul docs and learnt enough to start writing it on my own. I never got around to re-implementing OpenZeppelin libraries cuz I had the insane idea of implementing the EVM itself from scratch, in the legendary language JavaScript (well TypeScript actually, but it doesn’t have the same effect does it?).

Tiviem

tea-vee-em, / ti : vi : εm /

A rudimentary implementation of the Ethereum Virtual Machine in Typescript.

April 22: Initial commit

On the first day, I got a basic bytecode parser working and a figured out how I wanted to go about implementing each of the opcodes. The parser could step over the bytecode and increment the program counter appropriately (kinda) and for the opcode implementation I decided to use an object where each entry would be like so:

const instructions = {

'01': {

opcode: '01',

name: 'ADD',

minimumGas: 3,

implementation: (a: bigint, b: bigint) => [a + b],

},

'02': {...},

'03': {...},

}Over the next few days I worked on implementing other arithmetic opcodes and PUSH opcodes. Here’s where I encountered the first issue with my implementation.

See the interface of the instructions object, ADD takes in a and b and returns a value that gets pushed onto the stack. This works for opcodes that take in two args and return one value (ADD, SUB, MUL, DIV), but fell apart when I had to read arguments from the bytecode instead of the stack (PUSH family). So for PUSH I had to create an escape hatch in the bytecode parser that would enable me to read the args off the bytecode.

Stuff like this kept piling on and I had to use // @ts-ignore a lot which broke my auto-complete. But I finally rewrote it when I had to implement the SWAP family. SWAP doesn’t just interact with the top of the stack, it may have to go 16 indices deep and rearrange the stack.

The problem was the that I separated the implementation of the opcodes from the part that would read arguments from the stack. This worked for stuff like ADD that reached two slots deep and only pushed values, but would cause a lot of issues when working with stuff like SWAP that not only pushed but also re-arranged values on the stack. So I rewrote it such that the implementation is responsible for consuming the arguments off the stack or the bytecode.

0x01: {

name: 'ADD',

minimumGas: 3,

implementation: ({ stack, counter }) => {

const tempStack = stack.map(s => s);

const a = tempStack.pop();

const b = tempStack.pop();

if (!(typeof a == "bigint" && typeof b == "bigint")) return {

stack: [...tempStack],

counter: counter+1,

continueExecution: false,

error: "Stack underflow"

};

const newStack = tempStack.concat(BigInt.asUintN(256, a + b))

return {

stack: newStack,

counter: counter+1,

continueExecution: true,

error: null

};

},

},A bit verbose, but each instruction has the same interface consuming InstructionInput and returning InstructionOutput.

type InstructionInput = {

stack: readonly bigint[],

memory: Uint8Array,

gas: number,

bytecode: Uint8Array,

counter: number

}

type InstructionOutput = {

stack: bigint[],

counter: number,

continueExecution: boolean

error: string | null,

memory?: Uint8Array,

additionalGas?: number,

}Theoretical Gaps

There are two kinds of programmers (mostly):

- The guy who learnt programming in college using Java or C, has strong fundamentals and can explain explain how a computer works in 5 different levels of difficulty.

- The guy who learnt programming online using Javascript or Python, learns stuff as they go and cannot explain how a computer works.

I fall into camp number two. Like many of us, I learnt programming to hack NASA. Anyway, because I

learnt stuff “as I went along”, I skipped a lot of the fundamentals. I never learnt much about

binary, bits, core data-types and such. This left a huge knowledge gap which was a bit disorienting

when I was trying to figure out the difference between DIV and SDIV.

Luckily, I managed to learn some of these concepts “as I went along” and will be willfully ignorant of the electrons dancing in my computer until I have to simulate quantum computers in Javascript.

W1nt3r’s tests

Though evmfromscratch isn’t out yet, w1nt3r has a repo with a lot of tests for validating evm implementations. The tests have been really useful.

Program Counter and Strings

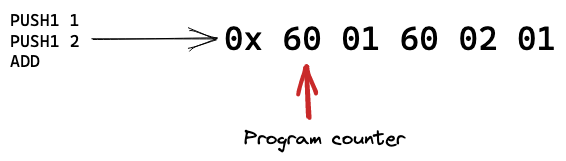

The program counter keeps track of where we are in the bytecode and which command to execute next.

The arrow represents the program counter

Initially the bytecode parser iterated over a string. This was pretty easy as a rough draft of the implementation as it’s just good ol’ string. But because each byte is represented by two characters in hex, the program counter had to be incremented by two, instead of one, and needed other arithmetic gymnastics when dealing with the PUSH family. While implementing JUMP, I finally switched over to Uint8Array to represent the bytecode. Here each array element is of 8 bits (1 byte) and represents 1 opcode (or 1 byte of arguments). So now the program counter has to be incremented by one and doesn’t need any arithmetic gymnastics.

Once I learned about Uint8Array it made sense to use it in a lot of places. I use it for memory too now.

***

I’ve implemented all the stack manipulation, arithmetic, comparison, memory, control-flow opcodes. Mostly now I need to handle the context/environment related opcodes, stuff like ADDRESS, GAS and storage. I have no idea how I’m gonna do it, but it’ll be fun.

This is project has been fantastic. I can’t imagine any other project that has taught me so many different things while building it and I’m excited to continue working on this.